Gelukkige verjaardag, Milan Kundera (1 april 1929). Net vandaag diept Bruno Maçães een artikel op dat Kundera in 1984 publiceerde in The New York Review of Books.

Vanuit het perspectief van wat vijf jaar na de publicatie gebeurde, en vandaag in Oekraïne en Europa, is The Tragedy of Central Europe (registratie vereist, pdf hier) buitengewoon interessant.

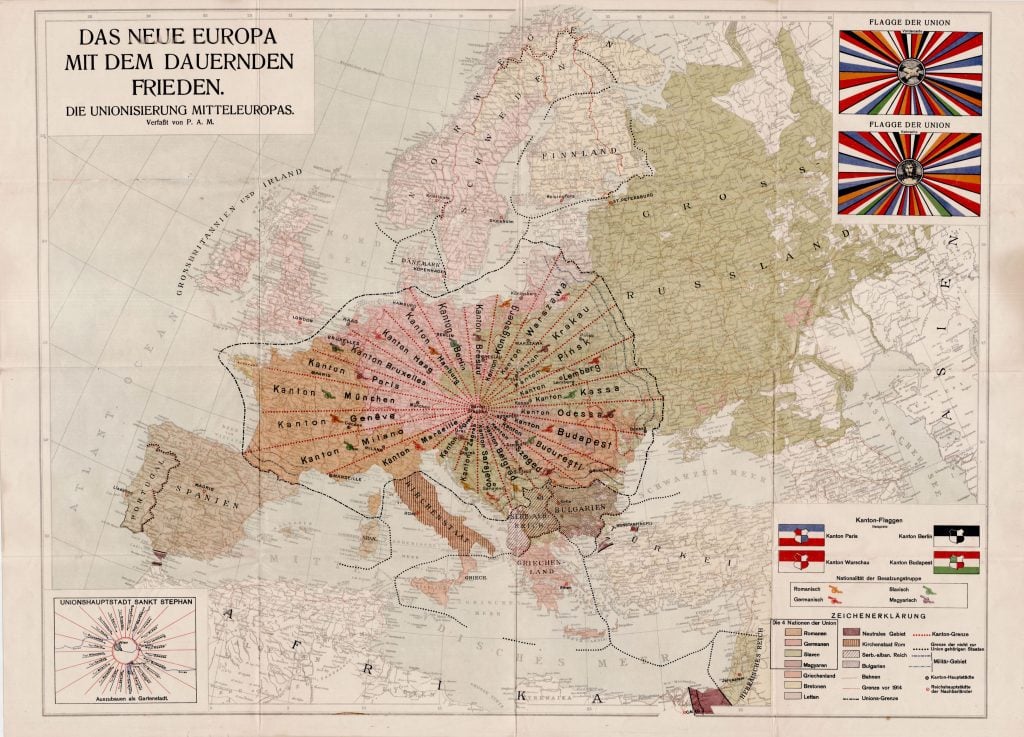

De tragedie van Centraal-Europa, schrijft Kundera (in 1984!), is dat “these countries have vanished from the map of the West.” En vooral: “Why has this disappearance remained invisible?”

De Centraal-Europese landen behoorden cultureel tot West-Europa, maar politiek tot Oost-Europa, terwijl ze eigenlijk de kiem van wat Europa vandaag is of tracht te zijn in zich droegen:

Central Europe longed to be a condensed version of Europe itself in all its cultural variety, a small arch-European Europe, a reduced model of Europe made up of nations conceived according to one rule: the greatest variety within the smallest space. How could Central Europe not be horrified facing a Russia founded on the opposite principle: the smallest variety within the greatest space?

En dan, met bijna griezelig vooruitzicht:

Indeed, nothing could be more foreign to Central Europe and its passion for variety than Russia: uniform, standardizing, centralizing, determined to transform every nation of its empire (the Ukrainians, the Belorussians, the Armenians, the Latvians, the Lithuanians) into a single Russian people.

En in een voetnoot:

One of the great European nations (there are nearly forty million Ukrainians) is slowly disappearing. And this enormous, almost unbelievable event is occuring without the world realizing it.

Waarom is deze verdwijning onzichtbaar gebleven?

Een deel van de verklaring ligt in de landen zelf:

The history of the Poles, the Czechs, the Slovaks, the Hungarians has been turbulent and fragmented. Their traditions of statehood have been weaker and less continuous than those of the larger European nations. Boxed in by the Germans on one side and the Russians on the other, the nations of Central Europe have used up their strength in the struggle to survive and to preserve their languages. Since they have never been entirely integrated into the consciousness of Europe, they have remained the least known and the most fragile part of the West—hidden, even further, by the curtain of their strange and scarcely accessible languages.

In een wereld die geopolitiek en geschiedenis probeerde te versimpelen tot een strijd of evenwicht tussen grote machtsblokken, waren de Centraal-Europese landen outsiders die tussen de plooien vielen:

The people of Central Europe are not conquerors. They cannot be separated from European history; they cannot exist outside it; but they represent the wrong side of this history; they are its victims and outsiders. It’s this disabused view of history that is the source of their culture, of their wisdom, of the “nonserious spirit” that mocks grandeur and glory. “Never forget that only in opposing History as such can we resist the history of our own day.” I would love to engrave this sentence by Witold Gombrowicz above the entry gate to Central Europe.

Maar de onzichtbaarheid van het verdwijnen van de Centraal-Europese landen zegt ook iets over een blinde vlek in (West) Europa. Centraal-Europa was misschien, na het einde van het Habsburgse rijk in 1918, een politieke outsider geworden; het bleef toch een bakermat van Europese cultuur? Musil, Kafka, Zweig, Kraus, Canetti, Gombrowicz, Freud, Wittgenstein, Loos, Klimt, Mahler, Schönberg, Bartók, Janáček en zelfs het Zionisme. De lijst kan gemakkelijk dubbel zo lang worden. Is het toevallig dat deze bakens en bakers van wat toch Europese cultuur is, leefden en werkten in dezelfde periode, in dezelfde regio (stad zelfs)?

Dus, vraagt Kundera:

The disappearance of the cultural home of Central Europe was certainly one of the greatest events of the century for all of Western civilization. So, I repeat my question: how could it possibly have gone unnoticed and unnamed?

The answer is simple: Europe hasn’t noticed the disappearance of its cultural home because Europe no longer perceives its unity as a cultural unity.

Zo komen we tot de vraag die ons ook vandaag nog moet bezighouden:

In fact, what is European unity based on?

Kundera, zo moet hij toegeven, heeft geen antwoord. Het was ooit religie; dan werd het cultuur. Maar nu?

I don’t know, I know nothing about it. I think I know only that culture has bowed out.

Cultuur heeft zich teruggetrokken, met een buiging.

En hij vertelt de droevige anekdote over hoe hij met een beroemde Tsjechische filosoof door Praag wandelde, vlak nadat diens manuscript van duizend pagina’s in beslag genomen was door de politie, het werk van tien jaar. Ze overwogen een open brief te sturen naar een algemeen erkende, grote Europese culturele persoonlijkheid.

But who was this person?

Suddenly we understood that this figure did not exist. To be sure, there were great painters, playwrights, and musicians, but they no longer held a privileged place in society as moral authorities that Europe would acknowledge as its spiritual representatives. Culture no longer existed as a realm in which supreme values were enacted.

Zijn vriend stuurde de brief uiteindelijk toch, naar Jean-Paul Sartre, en hij kreeg zijn manuscript terug.

Maar now his letter would no longer find a recipient.

We hebben bij elk citaat (in 1984!) bijgedacht. Maar hoe is het vandaag?

Kundera besluit (in 1984!):

After having been torn away from Europe in 1945, does Central Europe still exist?

Yes, its creativity and its revolts suggest that it has “not yet perished.” But if to live means to exist in the eyes of those we love, then Central Europe no longer exists. More precisely: in the eyes of its beloved Europe, Central Europe is just a part of the Soviet empire and nothing more, nothing more.

Sinds 1989 maken de landen van Centraal-Europa weliswaar geen deel meer uit van het Soviet empire. Maar wat is de huidige status van de regio in the eyes of its beloved Europe?

Een zoek op “voormalig oostblok*” op de sites van De Standaard en de Tijd levert nog vele honderden resultaten op. De jongste jaren lijkt die connotatie wel te verminderen. Maar staat Centraal-Europa ondertussen wel op de map?